An update on issues of concern to the Asian American and Pacific Islander community and activism on the Stanford campus.

The nation elected its first female, Black and South Asian vice president, Kamala Harris, currently a California senator. Her mother, Shyamala Gopalan, immigrated from India to the United States, where she was a cancer researcher and civil rights activist. Her father, Donald Harris, from Jamaica, is professor emeritus of economics at Stanford University. Gopalan and Harris met as student activists at UC Berkeley.

The election saw increased Asian American voter turnout, with much higher rates of early and absentee voting in major battleground states, compared to 2016. Political observers suggested that Asian Americans might swing key races, with an estimated “third of all AAPI voters liv[ing] in the 10 most competitive states.” Ultimately, the majority of Asian American voters supported Biden (63%) to Trump (31%), according to an NBC News Exit Poll, while a CNN survey showed Biden (61%) to Trump (34%).

However, the label of “Asian American” includes more than 19 different ethnicities, so the reality is more complicated. As noted in Vox, “AAPI voters’ alignment with the political parties varies quite significantly, with a high proportion of AAPI voters identifying as unaffiliated.” (More survey data here at AAPI Data, broken down by ethnic group.) While the majority of Asian Americans overall voted for Biden, some ethnic communities appeared to shift toward Trump, with motivations partly rooted in geopolitics as well as culture. “What is surprising is that I would have expected a noticeable decline in the percentages [of Asian American votes] given Trump's xenophobic and anti-immigrant rhetoric”—especially during COVID—but that repudiation of the president didn’t happen, observed UCLA Professor Paul Ong.

Part of the problem is that “Asian American” can be a nebulous term, and statistics are rarely disaggregated by ethnic community. Language also poses a barrier to accurate polling. Despite increased outreach to Asian Americans by presidential campaigns in 2020 (see initiatives from Biden and Trump), spending was focused “only in the last six weeks of the election cycle,” according to Janelle Wong of AAPI Data. “This is typical and has been the case our whole lives. No one pays attention to Asian Americans until the weeks before an election...Consistent, long-term investment could make a difference, but it's just not the way that campaigns operate.”

Writing in The New York Times, Jay Kaspian Kang calls for a more nuanced approach to connecting with Asian American voters. He suggests many first-generation immigrants may not identify with the “Asian American” label—they have priorities other than representation in media and national institutions, which is largely a concern of younger (frequently second- and third-generation) Asian Americans. He advises against treating Asian voters as a “monolithic” bloc, and warns against “taking them for granted.” New political alignments may be needed to cultivate the support of the country’s fastest-growing racial/ethnic group—the AAPI population grew from 11.9 million in 2000 to 20.4 million in 2015, or an increase of 72%. Of particular relevance, people of Asian descent also represent the fastest-growing group of eligible voters.

In California, there were divided views among Asian Americans on Proposition 16, which would have allowed race and gender-based affirmative action in the state. The proposition was ultimately rejected 57.2% to 42.8%.

The Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus sent a letter to the Biden campaign asking that AAPI appointees make up at least 7% of the Cabinet, in reflection of the community’s share of the overall population. Congresswoman Judy Chu told NBC Asian America that a failure to appoint anyone from the community would send a “terrible message that being inclusive does not require including AAPIs.”

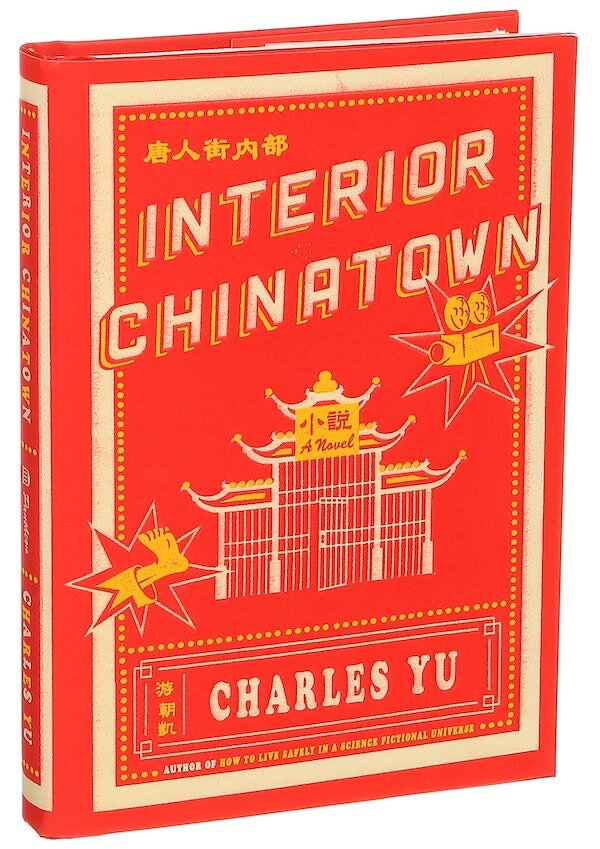

Charles Yu, a Taiwanese American author, won the 2020 National Book Award for the novel “Interior Chinatown”. His humor-laden take features an Asian protagonist—also Taiwanese American—who is “relegated to background roles such as Generic Asian Man, Silent Henchman, and Delivery Guy” in a Hollywood television production. According to Yu, the book explores how “Asians have been excluded...from being Americans for decades.” Transcending parental pressure, Yu transitioned away from a 13-year career as a corporate lawyer to become a full-time writer of novels, screenplays and short stories.

Asian American Studies Working Group

In response to student activism, Stanford created the Asian American Studies major in 1997. However, alumni are often surprised to learn that more than 20 years later, the Asian American Studies Program still has no full-time, tenured professors of its own; and certain critical courses have been offered only on an occasional basis. The Program is striving hard to meet tremendous student demand, but alumni must join their voices with those of students, staff and faculty to help create a stable home for Asian American Studies at the university.

To lend your support or simply to learn more, you are invited to join the Asian American Studies Working Group, an initiative of the SAPAAC Advocacy & Education Committee. Please e-mail asianamerican.workinggroup at gmail.com for an invitation to attend our next Working Group meeting.

— Visit www.sapaac.org/issues-advocacy for other editions of Asian American Issues